Mental-health struggles have risen sharply among young Americans, and parents and lawmakers alike are scrutinizing life online for answers.

James Donaldson on Mental Health - Has Social Media Fueled a Teen-Suicide Crisis?

By Andrew Solomon

A majority of Americans think social media is contributing to surging youth depression. Some researchers aren’t so sure.

Lori and Avery Schott wondered about the right age for their three children to have smartphones. For their youngest, Annalee, they settled on thirteen. They’d held her back in school a year, because she was small for her age and struggled academically. She’d been adopted from a Russian orphanage when she was two, and they thought that she might possibly have mild fetal alcohol syndrome. “Anna was very literal,” Lori told me when I visited the family home. “If you said, ‘Go jump in a lake,’ she’d go, ‘Why would he jump in the lake?’ ”

When Anna was starting high school, the family moved from Minnesota to a ranch in eastern Colorado, and she seemed to thrive. She won prizes on the rodeo circuit, making friends easily. In her journal, she wrote that freshman year was “the best ever.” But in her sophomore year, Lori said, Anna became “distant and snarly and a little isolated from us.” She was constantly on her phone, which became a point of conflict. “I would make her put it upstairs at night,” Lori said. “She’d get angry at me.” Lori eventually peeked at Anna’s journal and was shocked by what she read. “It was like, ‘I’m not pretty. Nobody likes me. I don’t fit in,’ ” she recalled. Though Lori knew Anna would be furious at her for snooping, she confronted her. “We’re going to get you to talk to a counsellor,” she said. Lori searched in ever-widening circles to find a therapist with availability until she landed on someone in Boulder, more than two hours away. Anna resisted the idea, but once she started she was eager to keep going.

Nonetheless, the conflicts between Anna and her parents continued. “A lot of it had to do with our fights over that stupid phone,” Lori said. Anna’s phone access became contingent on chores or homework, and Lori sometimes even took the phone to work with her. “I mean, she couldn’t walk the horse to the barn without it,” Lori said. Lori understood that the phone had become a place where her daughter sought validation and community. “She’d post something, and she’d chirp, ‘Oh, I got ten likes,’ ” she recalled. Lori asked her daughters-in-law to keep an eye on Anna’s Instagram, but Anna must have realized, because she set up four secret accounts. And, though Lori forbade TikTok, Anna had figured out how to hide the app behind a misleading icon.

As Anna grew older, she became somewhat isolated socially. At school, jocks reigned and some kids had started drinking, but Anna was straitlaced and not involved in team sports. Still, there was good news. Early in her senior year, in the fall of 2020, she landed the lead in the school play and was offered a college rodeo scholarship. “But anxiety and depression were just engulfing her,” Lori said. Like many teen-age girls using social media, she had become convinced that she was ugly—to the point where she discounted visual evidence to the contrary. “When she saw proofs of her senior pictures, she goes, ‘Oh, my gosh, this isn’t me. I’m not this pretty.’ ” In her journal, she wrote, “Nobody is going to love me unless I ‘look the part.’ I look at other girls’ profiles and it makes me feel worse. Nobody will love someone who’s as ugly and as broken as me.”

Because senior year was unfolding amid the disruptions of the COVID pandemic and everyone was living much of their lives online, her parents decided to be more lenient about Anna’s phone use. Soon, she was spending much of the night on social media and saying she couldn’t sleep. Shortly before Thanksgiving, Lori and Avery went to Texas to visit their eldest son, Cameron, and his wife and young son. Anna was going to go, too, but changed her mind because of the risk of getting COVID close to the play’s opening night. Rather than leave her alone, Anna’s parents had her stay with her other brother, Caleb, who was nine years older and lived near the family ranch with his wife.

Get Support

If you are having thoughts of suicide, call or text 988 or chat at 988Lifeline.org.

In Texas, there was happy news: another grandchild was on the way. During a family FaceTime on Sunday, November 15th, Anna seemed thrilled at becoming an aunt for the second time. Afterward, she went to the ranch to check on the chickens. Caleb’s wife asked if she’d be back for dinner, but Anna said she’d stay put, given that her parents would return that night.

Lori and Avery were driving back to Colorado when a neighbor’s number popped up on Lori’s phone. She didn’t answer until the second call. The neighbor was too upset to say what had happened. Lori asked about Anna, and the neighbor kept repeating, “I’m sorry.” It turned out that she’d heard from a teacher whom Anna had phoned in distress and, when the neighbor went to check on Anna, she discovered that she’d shot herself. Now a sheriff’s deputy had arrived. Avery got him on the phone and asked, “Just tell us, is she alive?” The deputy replied, “No.” The Schotts drove on in terrible silence. As they crossed the prairie, a shooting star fell straight ahead of them.

Anna was buried on a hill at the family ranch. One of the rodeo cowboys brought a wagon to carry her ashes, and thirty other cowboys rode behind her. The ceremony has been viewed online more than sixteen thousand times. “So you know she made an impact,” Lori said.

Several months later, Lori heard from Cameron, who had read about the congressional testimony of a former product manager at Facebook named Frances Haugen. Haugen, who also released thousands of the company’s internal documents to the Securities and Exchange Commission and to the Wall Street Journal, claimed that the company knew about the harmful effects of social media on mental health but consistently chose “profit over safety.” (Meta—the parent company of Facebook and Instagram—has disputed Haugen’s claims.) Until Lori watched the testimony, she hadn’t really considered the role of social media in Anna’s troubles. “I was too busy blaming myself,” she recalled.

Lori began delving into Anna’s social-media accounts. “I thought I’d see funny cat videos,” she said. Instead, the feeds were full of material about suicide, self-harm, and eating disorders: “It was like, ‘I hope death is like being carried to your bedroom when you were a child.’ ” Anna had told a friend about a live-streamed suicide she had viewed on TikTok. “We have to get off social media,” she’d said. “This is really horrible.” But she couldn’t quit. A friend of Anna’s also told Lori that Anna had become fixated on the idea that, if her parents knew how disturbed she was, she’d be hospitalized against her will. That prospect terrified her.

Lori soon learned that other parents were suing tech companies and lobbying federal and state governments for better regulation of social media. Eventually she decided to do the same. “It takes litigation to pull back the curtain,” she explained. “I want those companies to be accountable. I don’t care about the money—I want transformation.”

Hundreds of lawsuits have been filed in relation to social-media platforms, including Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat, and TikTok. Families are not the only plaintiffs. Last year, Seattle’s public-school district sued multiple social-media companies alleging harm to its students and a resulting strain on district resources. Attorneys general for forty-one states and the District of Columbia have sued Meta for harming children by fueling social-media addiction. Both the United Kingdom and the European Union have recently enacted legislation that heightens companies’ responsibility for content on their platforms, and there is bipartisan support for similar measures in the United States. The surgeon general, Vivek H. Murthy, has called for a warning label on social-media platforms, stating that they are “associated with significant mental health harms for adolescents.”

Still, research paints a complex picture of the role of technology in emotional states, and restricting teens’ social-media use could cause harms of its own. Research accrues slowly, whereas technology and its uses are evolving faster than anyone can fully keep up with. Caught between the two, will the law be able to devise an effective response to the crisis?

Between 2007 and 2021, the incidence of suicide among Americans between the ages of ten and twenty-four rose by sixty-two per cent. The Centers for Disease Control found that one in three teen-age girls considered taking her life in 2021, up from one in five in 2011. The youth-suicide rate has increased disproportionately among some minority groups. Rates are also typically higher among the L.G.B.T.Q. population, teens with substance-abuse issues, and those who grow up in a house with guns.

Rates of depression have also risen sharply among teens, and fifty-three per cent of Americans now believe that social media is predominantly or fully responsible. Most American teen-agers check social media regularly; more than half spend at least four hours a day doing so. A 2019 study by researchers at Johns Hopkins University reported that spending more than three hours a day online can lead adolescents to internalize problems more, making it harder to cope with depression and anxiety. The authors of a 2023 report found that reducing social-media exposure significantly improves body image in adolescents and young adults. If you cannot distinguish between the “real” world and the virtual world, between what has happened and what is imagined, the result is psychic chaos and vulnerability to mental and physical illness. Facebook’s founding president, Sean Parker, stated in 2017, “God only knows what it’s doing to our children’s brains.”

Social media acts on the same neurological pleasure circuitry as is involved in addiction to nicotine, alcohol, or cocaine. Predictable rewards do not trigger this system nearly as effectively as unpredictable ones; slot-machine manufacturers know this, and so do social-media companies. “Teens are insatiable when it comes to ‘feel good’ dopamine effects,” a Meta document cited in the attorneys general’s complaint noted. Instagram “has a pretty good hold on the serendipitous aspect of discovery. . . . Every time one of our teen users finds something unexpected their brains deliver them a dopamine hit.” Judith Edersheim, a co-director of the Center for Law, Brain & Behavior, at Harvard, likens the effect to putting children in a twenty-four-hour casino and giving them chocolate-flavored bourbon. “The relentlessness, the intrusion, it’s all very intentional,” she told me. “No other addictive device has ever been so pervasive.”

Social-media platforms harness our innate tendency to compare ourselves with others. Publication of the number of likes, views, and followers a user garners has made social-media platforms arenas for competition. Appearance-enhancing filters may make viewers feel inadequate, and even teen-agers who use them may not register that others are doing the same. Leah Somerville, who runs the Affective Neuroscience and Development Lab, at Harvard, has demonstrated that a thirteen-year-old is likelier to take extreme risks to obtain peer approval than a twenty-six-year-old, in part because the limbic system of the adolescent brain is more activated, the prefrontal cortex is less developed, and communication between the two areas is weaker.

In 2017, the Australian discovered a Facebook document which, seemingly for advertising purposes, categorized users as “stressed,” “defeated,” “overwhelmed,” “anxious,” “nervous,” “stupid,” “silly,” “useless,” and “a failure.” The Wall Street Journal’s reporting on Meta’s internal documents indicated that management knew that “aspects of Instagram exacerbate each other to create a perfect storm”; that nearly one in three teen-age girls who felt bad about their bodies said that “Instagram made them feel worse”; that teen-agers themselves “blame Instagram for increases in the rate of anxiety and depression”; that six per cent of U.S. teens reporting suicidal ideation attributed it to Instagram; and that teen-agers “know that what they’re seeing is bad for their mental health but feel unable to stop themselves.” Last year, a former director of engineering at Facebook, Arturo Béjar, told Congress that almost forty per cent of thirteen-to-fifteen-year-old users surveyed by his research team said that they had compared themselves negatively with others in the past seven days.

Adam Mosseri, the head of Instagram, recently announced a set of safeguards designed to protect younger users, including making their profiles private and pausing their notifications at night. Still, social-media companies have been slow to enact meaningful overhauls of their platforms, which are spectacularly profitable. A notorious leaked Meta e-mail quoted in the attorneys general’s lawsuit announces, “The lifetime value of a 13 y/o teen is roughly $270 per teen.” Public-health researchers at Harvard have estimated that, in 2022, social-media platforms generated almost eleven billion dollars of advertising revenue from children and teen-agers, including more than two billion dollars from users aged twelve and younger. Proposed reforms risk weakening the grip on young people’s attention. “When depressive content is good for engagement, it is actively promoted by the algorithm,” Guillaume Chaslot, a French data scientist who worked on YouTube’s recommendation systems, has said. The Norwegian anti-suicide activist Ingebjørg Blindheim has described the dynamic as “the darker the thought, the deeper the cut, the more likes and attention you receive.”

In most industries, companies can be held responsible for the harm they cause and are subject to regulatory safety requirements. Social-media companies are protected by Section 230 of the 1996 Communications Decency Act, which limits their responsibility for online content created by third-party users. Without this provision, Web sites that allow readers to post comments might be liable for untrue or abusive statements. Although Section 230 allows companies to remove “obscene, lewd, lascivious, filthy, excessively violent, harassing, or otherwise objectionable” material, it does not oblige them to. Gretchen Peters, the executive director of the Alliance to Counter Crime Online, noted that, after a panel flew off a Boeing 737 max 9, in January, 2024, the F.A.A. grounded nearly two hundred planes. “Yet children keep dying because of Instagram, Snapchat, and TikTok,” she said, “and there is hardly any response from the companies, our government, the courts, or the public.”

One may sue an author or a publisher for libel, but usually not a bookstore. The question surrounding Section 230 is whether a Web site is a publisher or a bookstore. In 1996, it seemed fairly clear that interactive platforms such as CompuServe or Usenet corresponded to bookstores. Modern social-media companies, however, in recommending content to users, arguably function as both bookstore and publisher—making Section 230 feel as distant from today’s digital reality as copyright law does from the Iliad.

No court has yet challenged the basic tenet of Section 230—including the Supreme Court, which last year heard a case brought against Google by the father of a young woman killed in the 2015 ISIS attacks in Paris. The lawsuit argued that YouTube, a subsidiary of Google, was “aiding and abetting” terrorism by allowing ISIS to use the platform. Without addressing Section 230, the Justices ruled that the plaintiff had no claim under U.S. terrorism law. This summer, the Court declined to hear another case involving Section 230, though Justices Clarence Thomas and Neil Gorsuch dissented, indicating that they thought the section’s scope should be reconsidered. “There is danger in delay,” Thomas wrote. “Social-media platforms have increasingly used §230 as a get-out-of-jail free card.”

Advances in communications technology have always been disruptive. The historian Anne Applebaum points out that the invention of movable type enabled the religious wars of the seventeenth century, and that broadcast media fed both communism and fascism. She believes that it takes a generation to learn how to negotiate any new communication system. In Sam Shepard’s 1976 play “Angel City,” a character’s observations sound much like those of children in thrall to social media: “I look at the screen and I am the screen. I’m not me. I don’t know who I am. I look at the movie and I am the movie. I am the star. . . . I hate my life when I come down. . . . I hate being myself in my life which isn’t a movie and never will be.”

Safety and freedom lie at opposite ends of a spectrum. To deprive a child of all access to the Internet would be draconian and also impractical, given that young people are more tech-savvy than their parents. Teen-agers need privacy, but when their methods for hiding far outstrip their parents’ capacity to monitor their activity, children can die of that privacy.

When Chris Dawley was a high-school freshman, in the nineteen-seventies, in Wisconsin, his twenty-seven-year-old brother, Dave, troubled and addicted to cocaine, was working in Las Vegas. One day, Dave called their father asking to come home. After their father insisted that he be drug-free first, Dave shot himself. Years later, Chris shared the story on a first date with the woman who was to become his wife, Donna; she told him about the death of her fiancé in a workplace accident. Grief was a nexus of intimacy from the time they met, and Donna now thinks that this helped them after their son C.J. killed himself, in 2015, when he was seventeen. “We came together—we didn’t come apart,” she told me when I visited them, in Salem, Wisconsin. “We’d been through so much heartache before.”

From an early age, C.J. was remarkable. At two, he found a screwdriver and removed the doors of several kitchen cabinets. When he was thirteen, Donna came home to find a new computer all in pieces on her bedroom floor; he reassembled it completely by bedtime. Just three points short of a perfect score on his ACT, his mother recalled, C.J. was wooed by a recruiter from Duke; he wanted to be a nuclear engineer. He had a busy social life and was popular with girls. His high-school yearbook named him “funniest person.”

C.J. was given a smartphone his freshman year of high school. He spent a lot of time playing games and chatting with friends on Facebook, Instagram, and Snapchat. His mother recalled, “His phone was his life. We couldn’t sit at the table and have a meal without it.” He got a buzz when his posts received attention. Tall and handsome, he liked posting selfies, but, after commenters judged him skinny, he became self-conscious and determined to gain weight.

The girl to whom C.J. was closest was one he had met online; he told her, “Every time I think of going to college and the future, I just want to kill myself.” She told him to talk to someone. He said, “Well, I’m talking to you.” Neither of them knew what to do. He complained of terrible aches in his legs, which his doctor said were growing pains. He didn’t apply to Duke and was considering joining the Navy.

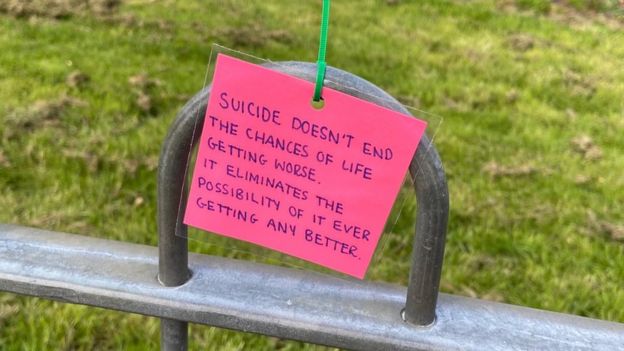

#James Donaldson notes:Welcome to the “next chapter” of my life… being a voice and an advocate for #mentalhealthawarenessandsuicideprevention, especially pertaining to our younger generation of students and student-athletes.Getting men to speak up and reach out for help and assistance is one of my passions.

https://standingabovethecrowd.com/james-donaldson-on-mental-health-has-social-media-fueled-a-teen-suicide-crisis/