How a therapy called CBITS helps children who have experienced trauma

Writer: Molly Hagan

Clinical Experts: Katie Peinovich, LCSW , Lisa H. Jaycox, PhD

What You'll Learn

- What is CBITS?

- What is cognitive behavioral therapy?

- How does cognitive behavioral intervention for trauma in schools (CBITS) help students?

- What is CBITS?

- Why treat trauma in schools?

- Who is CBITS for?

- How does CBITS work?

- Creating a trauma narrative

- Learning to share

- After CBITS

Research shows that childhood exposure to trauma is far more common than one might think, with two-thirds of kids having had at least one adverse experience and more than 1 in 5 having had three or more.

Living through an upsetting event can feel isolating — even when that event is shared, like a school shooting or a wildfire. (Because trauma is a clinical term, many clinicians don’t use the word traumatic until they understand the impact of the event on the child.) This is partly because people process events differently. And an event that is experienced as traumatic for one child may not be traumatic for another. But when a child does experience symptoms of trauma, it can affect their life and functioning in a host of ways.

“Trauma symptoms can be really, really disruptive to kids across many aspects of their lives,” says Katie Peinovich, LCSW, a licensed clinical social worker at the Child Mind Institute. Symptoms can affect kids in school and make it hard for them to think clearly, she says, and hurt their relationships with family and friends. Trauma symptoms also can affect their self-esteem and how they view themselves and the world.

“When you can alleviate some of those symptoms,” Peinovich says, “you can really increase a child’s level of functioning and help them feel safer.”

What is CBITS?

Over the last two decades, schools have become increasingly invested in addressing symptoms of trauma in their students through programs like CBITS — not to be confused with CBIT, a behavioral therapy for kids with tic disorders. A good way to remember is that the “S” in CBITS stands for schools.

Cognitive behavioral intervention for trauma in schools, or CBITS, is a school-based mental health program that helps kids manage symptoms of trauma.

Why treat trauma in schools?

Kids need to feel safe in order to learn, but offering trauma intervention services at school has other benefits, too. While there is effective individual therapy for children who have experienced trauma, called trauma-focused cognitive behavior therapy (TF-CBT), many children may not have access to it.

“The beauty of schools is that the kids are already there,” says Lisa H. Jaycox, PhD, a senior behavioral scientist at the RAND Corporation. Parents and caregivers don’t have to worry about finding a provider or transportation, paying for services, or scheduling appointments. And for kids, participating in a school-based program helps reduce the shame and self-blame that can come after a distressing event — nagging worries that there is something wrong with them or that they’re the only one reacting this way.

Kids who are struggling often don’t recognize that their problems are related to the trauma, which may have happened much earlier. “They feel like it’s just part of them, and they’re not really relating it back to the traumatic experience,” says Dr. Jaycox. “So, part of what we do is help kids understand how symptoms are related and how they can start to address them through different skills and coping strategies.”

Who is CBITS for?

CBITS is designed to meet the needs of children from kindergarten through high school who have been exposed to a disturbing event — even if they haven’t been clinically diagnosed with PTSD, as is most often the case.

Dr. Jaycox was instrumental in developing the CBITS program with the Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD) starting in the late 1990s. At the time, the district’s mental health services were strained. In some schools, “every single kid” reported having seen a gang assault, shooting, or death. LAUSD reached out to the RAND Corporation for help addressing their students’ needs on a larger scale. What is significant about CBITS, Dr. Jaycox notes, is that it was created and researched in tandem with scientists and the school.

The scientists worked with school-based social workers in diverse groups, which included recent immigrants. “So, we were dealing with multiple languages and cultures right from the beginning,” Dr. Jaycox says.

Dr. Jaycox and her colleagues brought the program to students in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina and worked with the National Native Children’s Trauma Center to adapt the CBITS manual for Native American youth. They also continue to adapt and evolve the program for kids in foster care and in different countries, including China, Guyana, and Japan.

How does CBITS work?

First, students are assessed to see if they would benefit from the program. Screenings look a bit different depending on the school, but clinicians are looking for kids who 1) have been exposed to an upsetting event and 2) are continuing to experience symptoms of distress. Screenings are meant to catch moderately severe but subtle symptoms that even the most attentive teachers or caregivers might have missed.

Trauma symptoms

Right after an upsetting event, most people experience some symptoms of trauma that might include the following:

- Feeling really anxious or on edge (hyperarousal), jumping at any sudden noise or movement

- Re-experiencing the event through nightmares, intrusive thoughts, or flashbacks

- Avoiding thinking or talking about the event because it stirs up too many intense emotions

- Experiencing mood changes, or changes in the way the person thinks about themselves, other people, and the world

These symptoms can dissipate on their own. But if they persist for too long, it’s a sign a child might need extra help coping.

CBITS and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT)

CBITS programs are run by trained mental health professionals. (There is also a version called Support for Students Exposed to Trauma (SSET) designed to be implemented by nonclinical staff, like teachers.) Groups consist of 6 to 10 kids who meet in 45-minute sessions (the length of an average class period) once a week for 10 to 12 weeks.

Skills and strategies

CBITS incorporates aspects of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), which is based on the idea that if we can recognize how our feelings influence our thoughts, we can learn to better manage our behaviors.

In group sessions, kids learn relaxation skills, like breathing exercises they can use to calm down, but they also learn ways to address maladaptive thinking, Dr. Jaycox explains. For example, “Something bad happened to me, so I must be a bad person.” Or: “Someone hurt me, so I can’t trust other people.”

“We work on addressing those thoughts, challenging them, and trying to come up with a more realistic ways to think about it,” she says.

The program also targets avoidant behaviors. Say for example, a child was in a bad car accident. They may avoid traveling in a car or even crossing the street on the way to school. It’s OK to be afraid of things — but it becomes a problem when kids feel controlled by their fears.

“We develop a list of things that they may be avoiding because they’re trauma-related but otherwise are safe,” Dr. Jaycox says. “We develop a hierarchy of those things that are making them anxious. And then we work on approaching them in a safe way so that they can get used to them again and have that anxiety dissipate.”

Creating a trauma narrative

The CBITS program also includes up to three one-on-one sessions with a child and the clinician. Part of this work involves creating a trauma narrative.

Upsetting memories are often fragmented, which can cause anxiety, Dr. Jaycox explains. “Deliberately thinking about the event or writing about it makes it a more coherent memory and a more coherent story,” she says. “Creating a narrative is a kind of exposure and habituation to the trauma that helps kids feel more in control when they’re thinking about it” — lessening the anxiety that the memory carries over time.

To help kids understand the concept of habituation, Peinovich says she’ll sometimes ask if they’ve ever seen a scary movie.

“The first time you see it, it feels super, super scary. The jump scares are really surprising, and you don’t know what’s going to happen next,” Peinovich says, emphasizing the physical sensations — like feeling your heart race — that come with being afraid.

“But then the next time you see it, what is that like? You know when the jump scares are coming now. So maybe they still surprise you, but it’s not quite as bad. Or not quite as scary. And what about the third or fourth time?”

“It’s just sort of an illustration about the way that your emotions change the more you engage with something.”

Learning to share

The clinician also works with a child to decide how they want to share their experience in group sessions. Groups sessions are important because they help kids see that they’re not alone, even if their individual experiences are different. But descriptions are purposefully kept general, brief, and direct: “I was in a car accident,” or “I got hurt in a car accident.”

In group, the goal is the act of sharing, not processing the details. “We don’t want them to be carrying around each other’s traumatic experiences,” Peinovich says. “We want sharing to feel positive and supportive, not overwhelming.”

Talking about upsetting things is difficult, but providing kids with straightforward language helps them understand that it’s also safe and OK to do, Peinovich explains. In individual sessions, “we don’t want to make them worry that they’re going to overwhelm us with the information, or that what they’re talking about is something that is super bad or distressing to talk about,” she says.

“I think sometimes when you qualify too much — like, ‘I know this might be really hard, and this can be really uncomfortable to talk about’ — what you’re communicating to the child is, ‘Oh, this is a really big thing.’”

Peinovich says her goal is to separate the intensity of the feelings from the recounting: “Like, ‘Hey, this is a really hard experience that you had but it doesn’t mean anything bad about you. So, let’s talk about it.’”

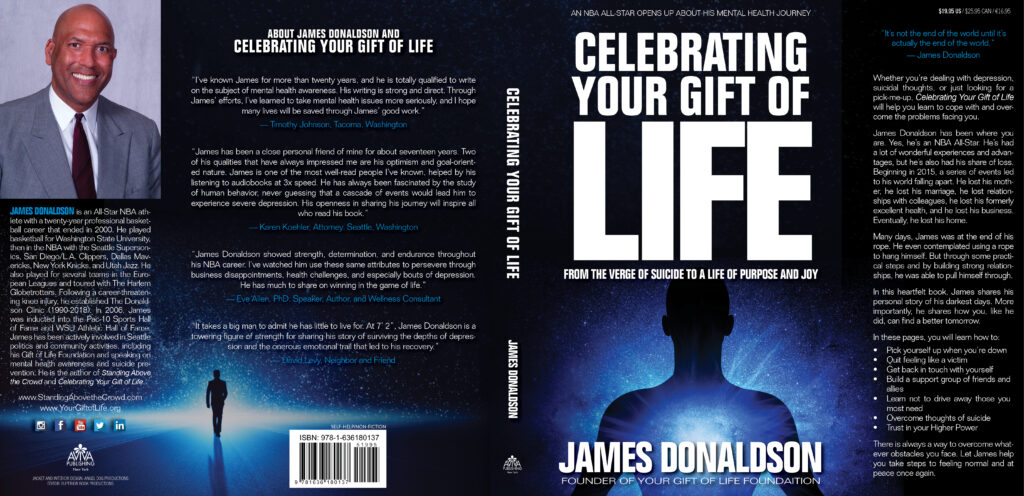

#James Donaldson notes:Welcome to the “next chapter” of my life… being a voice and an advocate for #mentalhealthawarenessandsuicideprevention, especially pertaining to our younger generation of students and student-athletes.Getting men to speak up and reach out for help and assistance is one of my passions. Us men need to not suffer in silence or drown our sorrows in alcohol, hang out at bars and strip joints, or get involved with drug use.Having gone through a recent bout of #depression and #suicidalthoughts myself, I realize now, that I can make a huge difference in the lives of so many by sharing my story, and by sharing various resources I come across as I work in this space. #http://bit.ly/JamesMentalHealthArticleFind out more about the work I do on my 501c3 non-profit foundationwebsite www.yourgiftoflife.org Order your copy of James Donaldson's latest book,#CelebratingYourGiftofLife: From The Verge of Suicide to a Life of Purpose and Joy

www.celebratingyourgiftoflife.com

Link for 40 Habits Signupbit.ly/40HabitsofMentalHealth

If you'd like to follow and receive my daily blog in to your inbox, just click on it with Follow It. Here's the link https://follow.it/james-donaldson-s-standing-above-the-crowd-s-blog-a-view-from-above-on-things-that-make-the-world-go-round?action=followPub

After CBITS

CBITS is an intervention, not an ongoing treatment plan. The goal is to help kids gain control of their symptoms, referring them elsewhere for other mental health needs, as necessary. Extensive research shows that programs like CBITS are effective, significantly reducing symptoms of PTSD and depression.

Peinovich, who has been delivering trauma services to kids for 25 years, says that she is continually struck by kids’ ability to bounce back from hardship with just a small amount of support.

“I came into this work with the idea that children are resilient and that they can get through a lot,” she says. “So, when I see that happen, it’s not necessarily like, ‘Oh wow, I can’t believe it!’ It’s more just like, ‘Wow, they really can do this!’”

Frequently Asked Questions

How to help a child with trauma symptoms in school? What is CBITS therapy?

CBITS (cognitive behavioral intervention for trauma in schools) is a school-based program that helps kids manage symptoms of trauma. In group and individual sessions with a clinician, kids learn skills to manage fear and anxiety caused by a disturbing experience.

https://standingabovethecrowd.com/james-donaldson-on-mental-health-cbits-trauma-treatment-for-kids-in-school/

Constance Lindsay is researching the connection between school discipline and the increasing rates of Black youth suicide.

Constance Lindsay is researching the connection between school discipline and the increasing rates of Black youth suicide.

Image: Unsplash

Image: Unsplash Image: Unsplash

Image: Unsplash