How parents can arm daughters to protect both their safety and their boundaries

Writer: Rae Jacobson

Clinical Expert: Dave Anderson, PhD

What You'll Learn

- Why do girls find it hard to respond to unwanted sexual attention?

- How can parents empower girls to push back against unwanted advances?

- How can parents help girls feel comfortable with saying “no”?

- Quick Read

- Full Article

- Take it seriously

- But don’t catastrophize

- Ditch the blame

- Help her set boundaries

- Pay attention to what she’s watching

- Talk about street harassment

- The dad dilemma

- Staying safe

- Be supportive

For many girls and women, unwanted sexual attention is a fact of life. This ranges from catcalls on the street to romantic or sexual advances that they don’t welcome. Many girls struggle with how to decline unwanted advances because they’re afraid of hurting someone’s feelings. And when the attention is aggressive or comes from someone older, it can be hard to know how to push back.

Parents can help girls protect both their safety and their boundaries. The first step is taking it seriously — not telling girls who feel uncomfortable or unsafe that they should just get over it. Instead, parents should focus on empowering girls to become their own advocates. An important way to empower her is to help her find — and practice — the words to use if someone isn’t respecting her boundaries. For example, she could say, “I don’t like that and I want you to stop.” Or, “I’m just not interested” or “I’m not comfortable doing that.”

Girls should understand that no one has the right to touch them if they don’t want it. That includes an arm around your shoulder, a kiss or any kind of sexual contact. It’s important for parents to help girls get comfortable with saying no.

For many girls, not being seen as mean or unfriendly is a major concern. Girls often get the message that to be liked, they have to be nice and accommodating and pleasing. But the message should be that anyone worthy of their attention should respect their feelings.

If something does happen — whether it’s a classmate who won’t take no for an answer, a pushy friend, or a stranger making lewd comments in the street — let your daughter know you have her back, even if she’s not ready to talk about it right away. When she is ready to talk, take her seriously and make it clear that you love and support her, no matter what.

“Hey beautiful, gimme a smile.”

“Why won’t you text me back???”

“I know you like me, even if you won’t say it.”

Sound familiar? If you’re female, the answer is probably yes.

Unfortunately, for the majority of women, unwanted sexual and romantic attention is a fact of life. Often beginning around puberty, it can range from awkward to annoying to downright terrifying. Many girls struggle with how to decline a romantic or sexual advance because they’re afraid of hurting someone’s feelings. And when the attention is aggressive or comes from someone older, it can be hard to know how to push back.

Parents can lay the groundwork to help girls protect both their safety and their boundaries by making sure they’re armed with healthy coping strategies.

Take it seriously

The first step to getting girls geared up to deal with unwanted attention is taking it seriously.

“What parents have to acknowledge is that from the moment their daughters hit puberty they’re likely to get attention,” says David Anderson, PhD, a clinical psychologist at the Child Mind Institute, “and that some of that attention, whether it’s a lewd comment from a stranger, or a boy who won’t take no for an answer, is going to be unwelcome, uncomfortable or even scary.”

While most parents, he says, are aware that unwanted attention happens, what some parents — especially dads who probably haven’t experienced it themselves — may not realize is how common, and how upsetting, it can be.

“We have a tendency to downplay these experiences,” says Stephanie Dowd, PsyD, a clinical psychologist. “But when we say, ‘Oh that’s no big deal, it happens to everyone,’ or suggest that it’s just part of life as a female, we’re implying that girls who feel victimized or upset are overreacting.” Instead, she says parents should send girls a clear message: “their feelings and boundaries are valid, and deserve to be respected.”

But don’t catastrophize

On the flip side, Dr. Anderson says, it’s also important to fight the urge to overreact. “As parents it’s natural to want to protect your child, but realistically you won’t be able to be by her side every day for the rest of her life,” he says. Tempting as it may be to hire a full-time bodyguard, parents should focus on empowering girls to become their own advocates.

“Part of staying safe and feeling comfortable is having the ability to recognize when something is making you feel uncomfortable or unsafe,” says Dr. Dowd, “And having the confidence to say, ‘What you’re doing is making me feel bad, and I don’t deserve that.’ ”

Ditch the blame

“One of the biggest mistakes we make when discussing unwanted attention is suggesting that women have somehow brought the problem on themselves,”’ says Dr. Anderson. “Girls who are sexually harassed are not causing the harassment, sexual harassers are. But many end up feeling that without knowing it, they’ve somehow brought this negative interaction on themselves by wearing the wrong outfit, or being ‘too nice.’”

One thing that makes girls more likely to feel they are to blame is the implication that their bodies are somehow dirty or shameful. “Body positivity is so important,” says Dr. Dowd. “If a girl gets the message that her body or sexuality is a bad thing, and then gets attention for it, she’s very likely to feel ashamed, or humiliated.” Likewise, she says, she is less likely to seek help if she experiences sexual harassment or assault.

In the end, Dr. Anderson says, the message needs to be, “This is not your fault and it should not be your problem, but in case someone behaves badly I want to make sure you have the tools to deal with it in a way that helps you feel, and stay, safe.”

Help her set boundaries

When it comes to setting boundaries parents should start — but not stop — with the basics. “First things first,” says Dr. Dowd. “No one has the right to touch you if you don’t want them to. Whether it’s an arm around your shoulder, a kiss or any kind of sexual contact.” Adds Dr. Anderson: “It’s important for parents to help girls get comfortable with saying no, even if they’re experiencing pressure from friends — or from the other person.”

For many girls, not being mean, or being perceived as mean or unfriendly, is a major concern — and a major pitfall, Dr. Dowd explains. “For example, if a boy has a crush on a girl but she doesn’t feel the same way she might think, ‘He’s a nice person, and I really don’t want to kiss him, but I don’t want to be mean…’” Or maybe she does have a crush on him, but she isn’t ready for the kind of relationship he wants. Telling him no can be hard because she might be afraid he’ll think she’s a prude, or won’t like her anymore..

Girls often get the message that to be liked they have to be nice and accommodating and pleasing. This, Dr. Dowd explains, results in “a struggle to feel like we’re deserving of our boundaries, especially when someone is questioning them.” It’s important to help girls understand that they don’t owe anyone attention, no matter how nice, or popular, or pushy a suitor may be. And any boy worthy of your attention should respect your feelings.

To help your daughter assess her feelings when things get tricky, try coming up with a mental checklist she can run through:

- Does this feel good or bad?

- Are you saying yes because you’re worried about hurting this person’s feelings?

- Does spending time with this person make you happy?

- Do you worry that asking this person to leave you alone could have consequences?

- Are your friends pressuring you to hang out with this person even though you’re not that interested?

- Is this person asking more from you — socially, romantically or sexually, than you feel comfortable giving?

Another important way to empower her is to help her find — and practice — the words to use if someone isn’t respecting her boundaries. For example, she could say, “I don’t like that and I want you to stop.” Or “I’m just not interested” or “I’m not comfortable doing that.”

Pay attention to what she’s watching

“A lot of girl-oriented media focuses on the narrative that being liked or getting attention from boys is something girls should aspire to and be grateful for,” says Dr. Dowd. “We want girls to take a second look at that and ask, ‘But…wait. Does she like him? Is she having any fun?’ ” Parents, she says, should work on helping girls become savvy consumers by teaching them to take a critical eye to media messaging. For example:

- Make time to watch your daughter’s favorite movies or shows together, and use the chance to point out examples of negative (and positive) romantic interactions. For example, “It seems to me like she’s said no a lot of times, but he won’t leave her alone. Does that seem okay to you?”

- Spotlight shows, books and movies that have an empowering message.

- Talk with her about what she reads, posts and watches on her social media feeds.

Talk about street harassment

According to the organization Stop Street Harassment, by the time most girls are in their teens up to 99% have experienced some form of public sexual harassment. “Being catcalled on the street may seem like no big deal, but for a lot of girls the harassment can be deeply unsettling,” says Dr. Dowd.

Parents should be careful not to normalize or dismiss harassment. “Street harassment may be common, but that doesn’t mean it’s okay,” notes Dr. Dowd: “If something happens, make sure your daughter understands that it’s not her job to grin and bear it. Parents can help by talking openly about street harassment and working together with girls to come up with a plan for how they’ll react if it happens. Some ideas could include:

- Asking another woman or a family to walk with her until she’s out of range. “These guys are yelling at me and making me feel uncomfortable. Could I walk with you to the end of the block?”

- Calling a friend or family member and staying on the phone until she feels safe.

- Going into a store or restaurant.

- Crossing the street.

- Taking a picture of the harasser with her phone.

- Calling the behavior out, if she feels safe responding in the situation, for example: “That’s disgusting and it makes me feel really bad.” “Actually, women hate this!”, “Would you talk to your own daughter like that?”

The dad dilemma

While most moms are likely no strangers to unwanted attention, the learning curve may be steeper for dads.

“Culturally, men just don’t get the same messages as women,” says Dr. Dowd. “They’re less likely to have experienced the scary side of unwanted attention, and for a lot of them, hassling or hitting on women might even be something they thought was just fun, or complimentary in the past.”

The reality, she says, is that for a lot of fathers, having a daughter may be the first time they find themselves having to imagine what these experiences are like for women. If dads find themselves struggling to understand why unwanted attention can be so upsetting, they can start by asking the women in their lives if they’d be willing share their own experiences of sexual harassment or unwanted attention.

Staying safe

As girls get older, it’s important to talk honestly about staying safe when they’re hanging out with their friends. Some common sense ground rules include:

- Avoiding alcohol and drugs.

- If she’s going to a party or concert, attending with a group of friends, and making an agreement to watch out for one another.

- Making sure her phone is on and charged, in case she needs to call for a ride or ask for help.

- Not accepting rides from strangers, even ones her own age.

- If someone is making her feel unsafe, make a scene: Get loud, and get out. Do whatever it takes to get away from the person and keep yelling until someone comes to help.

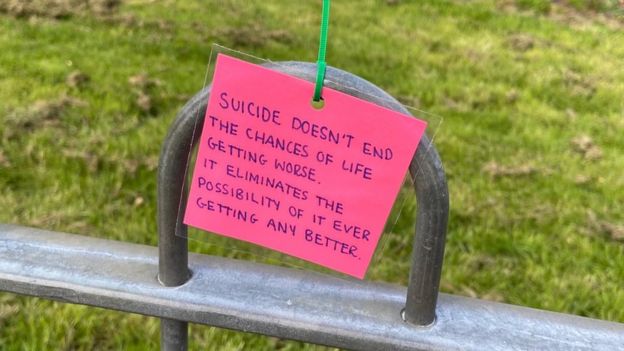

#James Donaldson notes:Welcome to the “next chapter” of my life… being a voice and an advocate for #mentalhealthawarenessandsuicideprevention, especially pertaining to our younger generation of students and student-athletes.Getting men to speak up and reach out for help and assistance is one of my passions. Us men need to not suffer in silence or drown our sorrows in alcohol, hang out at bars and strip joints, or get involved with drug use.Having gone through a recent bout of #depression and #suicidalthoughts myself, I realize now, that I can make a huge difference in the lives of so many by sharing my story, and by sharing various resources I come across as I work in this space. #http://bit.ly/JamesMentalHealthArticleFind out more about the work I do on my 501c3 non-profit foundationwebsite www.yourgiftoflife.org Order your copy of James Donaldson's latest book,#CelebratingYourGiftofLife: From The Verge of Suicide to a Life of Purpose and Joy

Click Here For More Information About James Donaldson

Be supportive

If something does happen — whether it’s a boy who won’t take no for an answer, a pushy friend or a stranger making lewd comments in the street — let your daughter know you have her back, even if she’s not ready to talk about it right away. “Let your daughter know that it’s okay not to feel okay,” says Dr. Dowd. “It’s common to have residual feelings about being harassed, and sometimes it takes a little while for the feeling to set in.” When she is ready to talk, take her seriously and make it clear that you love and support her, no matter what.

Frequently Asked Questions

How can parents help girls deal with unwanted attention?Why do girls have a hard time dealing with unwanted attention?

Many girls have a hard time dealing with unwanted attention because they do not want to be seen as mean or unfriendly. Girls often get the message that, to be liked, they must be accommodating and pleasing.

What should parents do if a girl is getting unwanted attention?

https://standingabovethecrowd.com/?p=15408